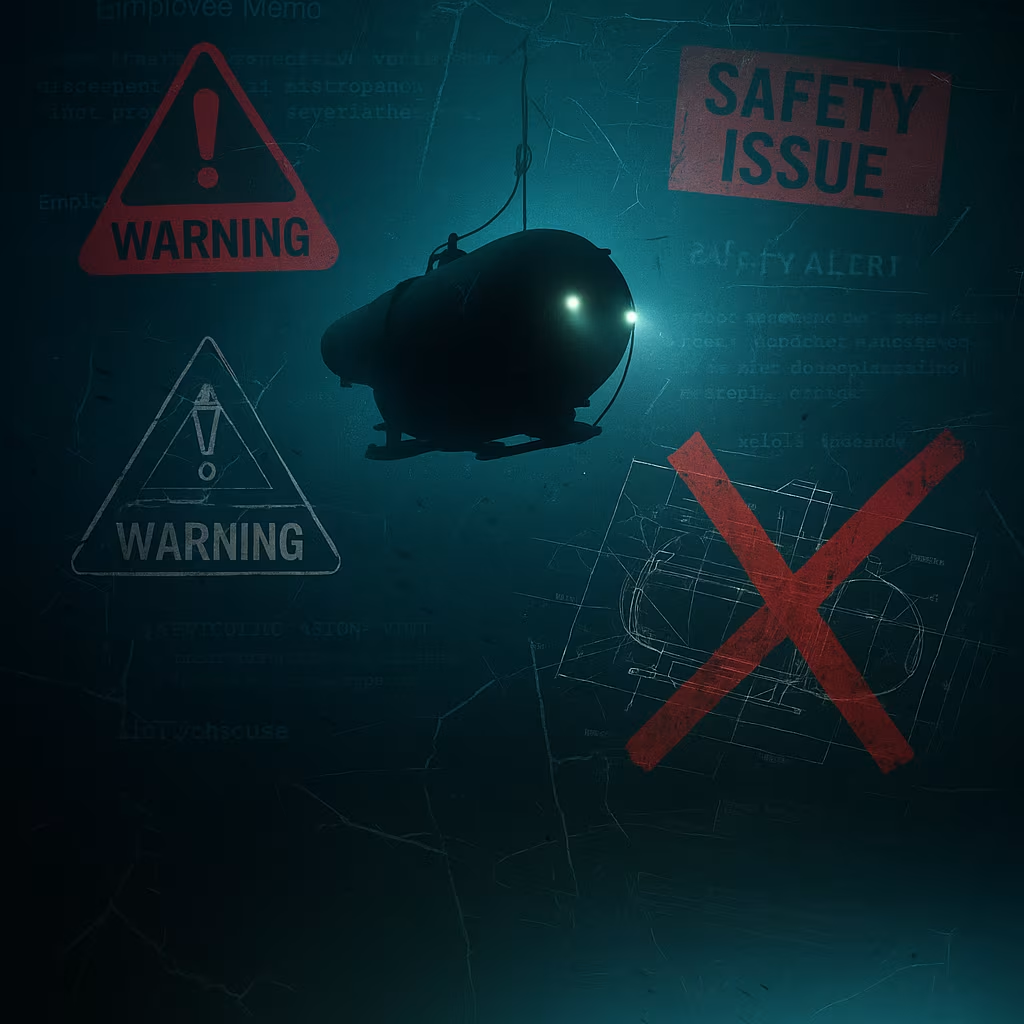

More than a year after the catastrophic implosion of the Titan submersible, a new report by the U.S. Coast Guard has shed disturbing light on what may have contributed to the tragedy. The report suggests that OceanGate’s internal practices—described as a “toxic workplace culture”—created an environment where safety concerns were downplayed, critical engineering standards were ignored, and dissenting voices were silenced.

The Titan, a deep-sea submersible owned and operated by OceanGate Expeditions, tragically imploded in June 2023 during a dive to the Titanic wreckage site, killing all five people on board. At the time, the incident sparked widespread scrutiny over the company’s unconventional design choices and regulatory loopholes. Now, the Coast Guard’s investigation goes even further, identifying internal culture as a key factor in the disaster.

Alarming Workplace Practices at OceanGate

According to interviews, internal documents, and testimony from former OceanGate employees, the company operated under a leadership style that discouraged questioning authority and pushed forward despite internal warnings.

The report describes a “culture of pressure and fear,” where engineers and technical staff felt hesitant to raise safety concerns about the Titan’s carbon-fiber hull or lack of industry-standard certification. In several cases, those who did speak up—either internally or publicly—were dismissed, ignored, or even terminated.

One of the most notable whistleblowers, David Lochridge, OceanGate’s former Director of Marine Operations, was fired in 2018 after warning that the submersible posed “serious safety concerns.” His termination, according to the Coast Guard’s findings, set a troubling precedent. From that point forward, employees reportedly feared retribution for challenging CEO Stockton Rush’s decisions.

Leadership Culture That Prioritized Speed Over Safety

Much of the blame centers on Rush himself, who perished in the Titan disaster. Known for his ambitious vision and willingness to take risks, Rush allegedly fostered an environment where speed, innovation, and media attention were prioritized above all else—even basic maritime safety standards.

The report cited internal communications where employees were pressured to meet expedition deadlines despite technical red flags. OceanGate’s decision to avoid classification from traditional certification bodies, like DNV or ABS, was described as emblematic of a “reckless” and “unregulated” engineering approach.

While OceanGate claimed this allowed for more agile innovation, multiple experts—including those interviewed by the Coast Guard—asserted that the lack of third-party validation left glaring safety gaps that ultimately contributed to the vessel’s catastrophic failure.

Ignored Warnings and Missed Opportunities

Former staff and outside advisors had repeatedly raised alarms about the experimental use of carbon fiber for deep-sea applications, which had never been proven safe at Titanic-depth pressures (~12,500 feet). The report confirmed that stress testing protocols were incomplete and often deprioritized due to scheduling constraints.

Additionally, the lack of formal documentation—including proper risk assessments, quality assurance procedures, and routine inspections—was noted as a serious breach of industry best practices.

The investigation also found that the company’s emphasis on media coverage and customer-facing experiences created a distracting work environment. Engineers were often asked to support promotional efforts rather than focus on systems integrity and testing.

A Culture of Silence and Suppression

Perhaps the most damning conclusion was that OceanGate’s internal culture discouraged open communication, which is critical in high-risk industries like submersible engineering. Several employees reported being explicitly warned not to share safety concerns with outside parties or clients. In one instance, an engineer told investigators they were instructed to “avoid using the word ‘experimental’” when speaking to passengers.

The Coast Guard called this “a systemic failure of organizational safety culture,” noting that OceanGate lacked the basic hallmarks of a high-reliability organization. Without psychological safety or structured feedback loops, critical information was suppressed, leaving fatal flaws unaddressed.

The Bigger Picture: A Wake-Up Call for Private Exploration

While OceanGate is no longer in operation, the Titan disaster and its surrounding circumstances are prompting broader discussions about oversight in private deep-sea exploration and adventure tourism.

The U.S. Coast Guard’s findings have already led to calls for stricter regulatory frameworks covering non-classified submersible vehicles, especially those carrying paying passengers. Lawmakers and maritime experts say the report reveals a dangerous gap in how experimental underwater technologies are monitored and approved.

The case also highlights the risks of “founder-led” innovation culture, where visionary leadership—while inspiring—can at times override essential safety protocols. Stockton Rush, a self-described disruptor, was praised by some for pushing boundaries, but the report now paints a picture of leadership that crossed into negligence.

A Preventable Tragedy

In its final assessment, the Coast Guard did not mince words: the Titan tragedy was “preventable.” The submersible’s design flaws were not the result of unpredictable ocean conditions but of deliberate decisions made within a corporate environment that suppressed dissent and elevated speed over caution.

Five lives were lost—including CEO Stockton Rush, British businessman Hamish Harding, French diver Paul-Henri Nargeolet, and Pakistani father-son duo Shahzada and Suleman Dawood. For their families, the report provides painful validation that more could have been done to prevent the tragedy.

The Titan disaster stands as a somber warning about what happens when innovation outpaces accountability. While progress in deep-sea exploration is vital, it must be grounded in the principles of engineering ethics, safety, and organizational transparency.

OceanGate’s story is not just about a failed submersible. It’s about a failed culture—one that silenced concerns, ignored standards, and ultimately contributed to the loss of life. The haunting lesson is clear: in high-risk environments, culture is just as important as technology.