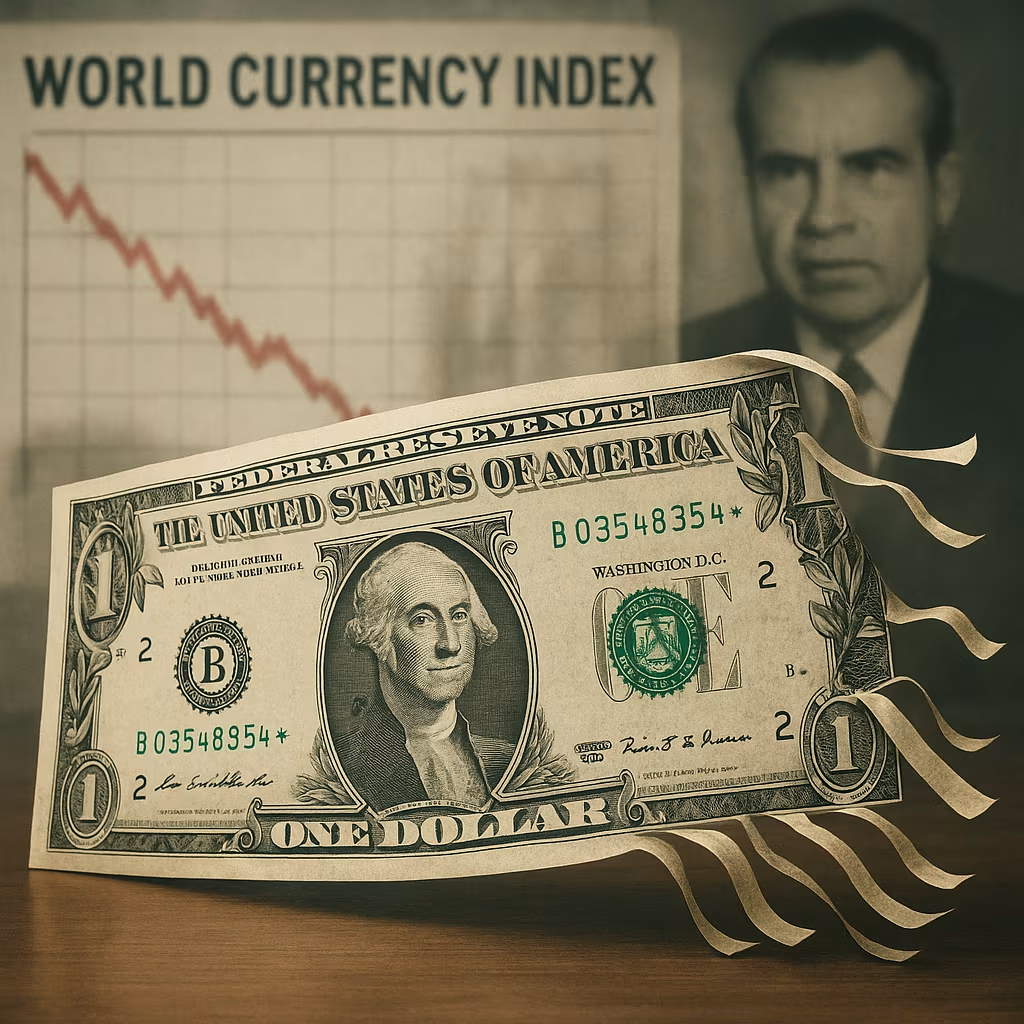

In a year marked by shifting global power dynamics and monetary policy pivots, the U.S. dollar has stumbled into uncharted territory. For the first half of 2025, the greenback posted its worst performance since the early 1970s—an era that famously ended the Bretton Woods system and saw President Richard Nixon sever the dollar’s link to gold. Fast forward more than five decades, and the dollar’s recent fall reflects a new set of global uncertainties, monetary recalibrations, and strategic realignments that threaten its dominance in the international financial system.

This article examines the reasons behind the dollar’s dramatic slump, the macroeconomic forces driving its weakness, and the potential consequences for global markets.

A Historical Comparison

To put the dollar’s 2025 decline into perspective, we must rewind to 1971, when President Nixon suspended the convertibility of the U.S. dollar into gold. That decision effectively dismantled the post-World War II global financial order. The dollar, once backed by a fixed amount of gold, became a free-floating currency subject to market forces.

Since then, the dollar has had its ups and downs, but it has largely retained its role as the world’s primary reserve currency. However, the first half of 2025 has witnessed a historic setback. The U.S. dollar index (DXY), which measures the dollar against a basket of major currencies, fell by nearly 9%—the steepest decline for any January-to-June period since the Nixon years.

What’s Driving the Decline?

1. Federal Reserve Policy Shift

After aggressive interest rate hikes throughout 2022 and 2023 to combat inflation, the Federal Reserve began easing policy in early 2025 as inflation cooled. This dovish pivot led to falling yields on U.S. Treasuries, making dollar-denominated assets less attractive to global investors. As rate differentials narrowed between the U.S. and other advanced economies, capital began flowing elsewhere.

2. Slower Economic Growth

The U.S. economy, which had remained resilient for much of the post-pandemic recovery, began to show signs of strain. Consumer spending slowed, job growth plateaued, and corporate earnings weakened in key sectors like tech and retail. These signals prompted concerns that the U.S. was heading toward a mild recession. Slower growth typically weighs on a currency as investor sentiment shifts toward safer or higher-yielding alternatives.

3. Global Reserve Diversification

A growing number of countries are reassessing their dependence on the U.S. dollar in response to geopolitical tensions and financial sanctions. Several central banks, especially in emerging markets, have been reducing their dollar exposure while increasing holdings in gold, euros, yuan, and other regional currencies. This trend is part of a broader movement known as “de-dollarization,” which weakens long-term demand for the greenback.

4. Trade Deficit and Fiscal Pressure

The U.S. trade deficit remained large in the first half of the year, driven by strong imports and weak exports. At the same time, rising fiscal deficits, fueled by entitlement spending and infrastructure outlays, have raised concerns about long-term debt sustainability. Foreign buyers have become more cautious about purchasing U.S. debt, putting additional pressure on the dollar.

5. Geopolitical Shifts

Tensions in Eastern Europe, the South China Sea, and the Middle East have led many investors to reconsider the traditional role of the dollar as a safe haven. Countries subject to sanctions or political isolation are seeking alternative payment systems and settlement currencies. Meanwhile, alliances like BRICS have accelerated efforts to create regional alternatives to the dollar-based trade system.

Impacts on Global Markets

The dollar’s weakness has far-reaching implications across global financial systems:

Emerging Markets: A weaker dollar provides relief to many developing countries that borrow in dollars. It lowers debt servicing costs and boosts local currencies, potentially improving financial stability.

Commodities: Since most commodities are priced in dollars, a falling dollar often results in higher prices for oil, gold, and industrial metals. This trend has already begun to fuel inflationary pressures in non-dollar economies.

U.S. Multinationals: A cheaper dollar can benefit American exporters by making their goods more competitive abroad. However, companies with significant import costs or overseas revenue exposure may suffer currency-related losses.

Investor Behavior: The dollar’s fall has driven investors toward alternative assets, including gold, cryptocurrencies, and foreign equities. Central banks are also reallocating reserves, gradually reducing their reliance on dollar holdings.

Could the Trend Continue?

While short-term technical factors could lead to a temporary rebound, many analysts believe the dollar’s downtrend could extend into the second half of 2025 and beyond. Unless the Federal Reserve shifts back toward tighter monetary policy or the U.S. economy stages a strong recovery, structural weaknesses may persist.

Moreover, as more countries seek alternatives to the dollar in trade and reserves, the global currency landscape could evolve into a more multipolar system. This would mark a major transition from the dollar-centric financial world that has dominated for nearly a century.

A Warning Sign or a Turning Point?

The dollar’s worst first-half performance in over 50 years is more than just a technical anomaly—it may signal the beginning of a long-term realignment in global finance. While the dollar is unlikely to be dethroned overnight, its gradual decline opens the door for competitors to gain ground, particularly in trade settlement and reserve allocation.

It also raises critical questions about U.S. economic policy, political stability, and fiscal discipline. If the dollar continues to lose ground without a credible plan to address underlying weaknesses, its role as the cornerstone of global finance could eventually be at risk.

The first half of 2025 marked a historic low for the U.S. dollar not seen since the Nixon administration. This slump is driven by a complex mix of monetary easing, slowing growth, geopolitical shifts, and global reserve diversification. While the immediate impact may appear manageable, the long-term implications for U.S. influence and financial dominance could be profound.

As the world adjusts to a new monetary reality, investors, policymakers, and businesses must prepare for a future where the dollar is no longer as dominant as it once was. Whether this decline proves to be a temporary stumble or a permanent pivot remains one of the most critical financial questions of our time.