In August 2023, global markets were rattled when Fitch Ratings downgraded the long-term credit rating of the United States from AAA to AA+. It was only the second time in history that the U.S. had lost its perfect sovereign credit score. The event may have passed without triggering a financial meltdown, but it served as a sobering reminder that even the most secure economies are not immune to fiscal scrutiny.

A credit downgrade may sound like a technical adjustment by rating agencies, but in today’s tightly interconnected financial system, such moves can have far-reaching consequences. Beyond reputational damage, downgrades affect interest rates, market confidence, and capital flows. When the downgraded entity is a major economic power or a systemically important financial institution, the event can ignite systemic risk—a chain reaction capable of destabilizing entire sectors or geographies.

As global debt continues to rise and fiscal conditions remain under pressure, the risks of further downgrades are real. Understanding the link between creditworthiness and systemic fragility is now more critical than ever.

What Is a Credit Downgrade?

A credit downgrade occurs when a credit rating agency—such as Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s (S&P), or Fitch—lowers the credit rating of a borrower, indicating increased risk of default or fiscal instability. The borrower could be a government, corporation, or financial institution.

For sovereign nations, a downgrade reflects concerns about:

- Rising debt levels relative to GDP

- Political dysfunction or inability to enact reform

- Erosion of fiscal credibility

- Slowing economic growth or structural weaknesses

Downgrades affect the cost of borrowing, as investors demand higher yields to compensate for increased risk. It also affects the eligibility of bonds for certain portfolios, particularly those managed by pension funds and central banks that require investment-grade assets.

How Credit Downgrades Trigger Systemic Risk

Systemic risk refers to the possibility that the failure or weakness of a single entity or market segment will cascade through the entire financial system, leading to widespread disruptions. A downgrade—especially of a key sovereign issuer or major financial institution—can act as a catalyst.

Here’s how:

- Increased Cost of Capital: Downgrades lead to higher interest payments on debt. For countries already facing fiscal stress, this can worsen deficits and lead to austerity or even default.

- Contagion in Bond Markets: When one country is downgraded, bondholders reassess similar markets, pulling money from other vulnerable economies.

- Collateral Calls: Lower-rated securities may no longer qualify as collateral in repurchase agreements or central bank facilities, causing liquidity squeezes.

- Forced Selling: Funds with mandates to hold investment-grade assets may be forced to sell downgraded securities, triggering sell-offs.

- Currency Instability: Downgrades often lead to capital outflows and currency depreciation, particularly in emerging markets.

- Erosion of Investor Confidence: A downgrade is a signal—not just about the specific issuer—but about broader structural weaknesses. This can impact consumer confidence and investor sentiment worldwide.

The U.S. Downgrade: A Warning, Not an Isolated Event

The U.S. downgrade by Fitch was not about an inability to repay debt, but rather a critique of governance. The agency cited “erosion of governance,” repeated debt ceiling standoffs, and rising deficits as reasons for the downgrade. Although Treasury yields rose modestly and equity markets briefly pulled back, the event served as a warning sign.

Other rating agencies, including Moody’s, have kept the U.S. at AAA but have issued cautionary notes. The lesson here is that no nation, regardless of its size or past reliability, is above scrutiny.

If future downgrades occur—especially in combination with rising interest rates or another economic shock—they could amplify systemic vulnerabilities already simmering beneath the surface.

Emerging Markets Are Especially Vulnerable

While developed economies like the U.S. or Germany may weather downgrades due to strong institutions and reserve currency status, emerging markets face more immediate consequences. Countries like Egypt, Pakistan, and Ghana have experienced downgrades that quickly escalated into full-blown crises involving:

- Sharp currency depreciation

- Collapse in investor confidence

- Skyrocketing bond yields

- Sovereign defaults or IMF bailouts

These events are not isolated. Due to global interconnectivity, a downgrade in a mid-sized emerging market can influence risk appetite globally, particularly in bond and foreign exchange markets.

Credit Downgrades and the Banking Sector

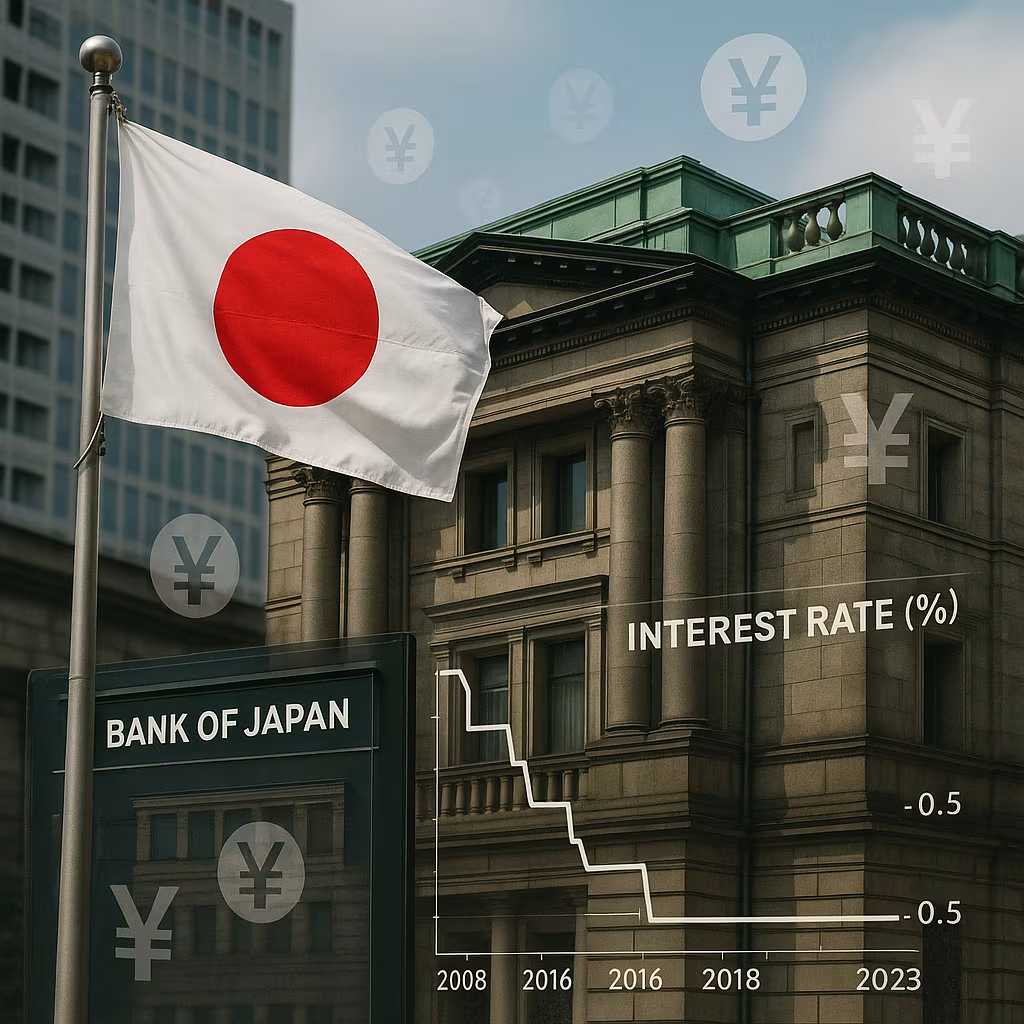

Another key systemic vulnerability lies in the banking system. Banks often hold large quantities of sovereign bonds. When the government’s credit rating is downgraded, the value of these holdings drops, affecting bank capital and liquidity.

In 2011, S&P’s downgrade of the U.S. was followed by downgrades of major U.S. banks, increasing funding costs and market stress. In countries where banks and governments are closely linked—a phenomenon known as the “sovereign-bank doom loop”—the effects can be especially severe.

Downgrades can also reduce the credit rating of state-owned enterprises or systemically important financial institutions, further amplifying the risk to the broader economy.

The Role of Investor Psychology

While credit ratings are based on quantitative analysis, their market impact is deeply tied to investor psychology. In stable times, investors may ignore ratings changes, especially if they see the downgrade as overly conservative. But during uncertain periods, even a one-notch downgrade can spark panic selling or a sudden revaluation of risk across multiple asset classes.

This is why timing and narrative matter. A downgrade during a market rally may be shrugged off. The same downgrade during a recession, monetary tightening cycle, or geopolitical crisis could have outsized consequences.

How to Mitigate Downgrade-Driven Systemic Risk

Governments, institutions, and investors can take several steps to reduce the likelihood and impact of downgrade-induced systemic risk:

- Proactive Fiscal Policy: Maintaining debt sustainability and showing commitment to reform can bolster credibility and stave off downgrades.

- Strengthening Central Bank Independence: Ensures market trust during periods of economic volatility.

- Improved Transparency and Communication: Clarifying fiscal intentions and debt servicing capabilities helps anchor investor expectations.

- Diversification of Investor Base: Encouraging long-term investors reduces susceptibility to panic selling.

- International Coordination: Especially in emerging markets, working with institutions like the IMF can help manage market expectations and avoid full-blown crises.

A Downgrade Is More Than a Symbol

In today’s global financial ecosystem, a credit downgrade is not just a technical event. It is a powerful signal—one that reverberates through bond markets, bank balance sheets, and monetary systems. When the downgraded party is a major economy or financial player, the stakes are even higher.

Systemic risk doesn’t always begin with a crash. Sometimes, it starts with a subtle shift in perception—when investors begin to question the financial health of an entity once seen as rock solid. Credit downgrades are often that shift. And when enough of them occur—or when one touches a critical node in the system—the entire architecture can be tested.

For governments and institutions, the message is clear: credibility, transparency, and fiscal prudence are not just best practices—they’re essential defenses against the next global shock.